Atomic-level crystal gazing: Revelation of crystallization mechanism enables fast writing of data to DVDs

Some 300 exabytes (3 × 1020 bytes) of information were stored in electronic media -- magnetic disks and tapes or optical disks -- throughout the world by 2007. Yet, the demand for electronic storage grows daily, driving an ever-increasing need to pack data into smaller volumes in quicker time. By studying how laser pulses alter the atomic structure of data-storage materials, a research team in Japan has uncovered a fundamental mechanism that could aid in the design of even faster information storage in the future1. The finding was published by Masaki Takata from the RIKEN SPring-8 Center, Harima, Shinji Kohara from the Japan Synchrotron Radiation Research Institute/SPring-8, Noboru Yamada from Panasonic Corporation and a team of scientists from Japan, Germany and Finland.

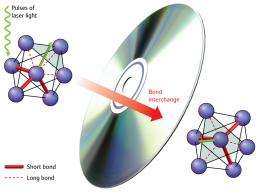

Rewritable memory, such as the random-access memory found in computers or on DVDs, is based on a phase change in specific types of materials in which the atoms change from one stable arrangement to another. Pulses of laser light can induce a phase change, a process known as ‘writing,’ and the material’s phase can be identified by ‘reading’ its signature optical properties.

To provide the first full understanding of the atomic structure of one such phase-change material, AgInSbTe (AIST)—often used in rewritable DVDs—Takata and his colleagues combined state-of-the-art materials-analysis techniques and theoretical modeling. A pulse of light can change AIST from an amorphous state, in which the atoms are disordered, into a crystalline phase in which the atoms are form an ordered-lattice structure. This process of crystallization happens in just a few tens of nanoseconds: the faster the crystallization, the faster data can be written and erased. No-one understood, however, why phase changes in AIST were so fast.

The teams’ analyses and modeling showed that AIST crystallizes in a different way to other commercially available phase-change materials. They found that crystallization of AIST is a simple process: the laser light excites the bonding electrons and causes them to move. A central atom of antimony (Sb) switches between one long (amorphous) and one short (crystalline) bond without any bond breaking (Fig. 1). “We hope to verify this bond-interchange model in the near future,” says Takata. “Crystallization is the storage-rate-limiting process in all phase-change materials, and an atomistic understanding of it is essential.”

The researchers also discovered that the absence of cavities within the crystal structure contributes to the faster writing speeds on AIST. This contrasts starkly with the alternative material germanium antimony telluride in which 10% of lattice sites in are empty.

More information: Matsunaga, T., et al. From local structure to nanosecond recrystallization dynamics in AgInSbTe phase-change materials. Nature Materials 10, 129–134 (2011).

Provided by RIKEN